For decades, productivity gains in aquaculture have been closely linked to feed, through improved formulations, higher digestibility and functional additives. Shellfish farming, however, follows a different logic. According to researchers involved in the BlueBio BIVALVI project, the main productivity gains for bivalves come not from added inputs, but from how production systems are managed.

The project is led by Nofima, with partners including the University of Bologna, University College Cork, Naturedulis and Norgeskjell, as well as collaborating partner Roaring Water Bay Mussels.

Unlike finfish, clams and mussels do not require compound feed. Their performance depends largely on water flow, natural food availability, biological timing and production decisions that are often considered secondary. Researchers involved in the project indicate that revisiting these everyday management choices can lead to measurable improvements in growth, production time and spat availability, without increasing inputs.

Infrastructure matters

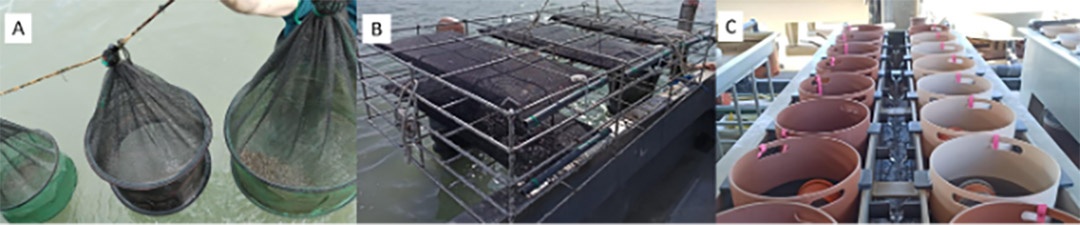

One of the clearest messages emerging from the project concerns the early handling of Manila clam spat. Comparisons between different pre-fattening systems — net lanterns, poches and on-land upwelling tanks — showed that growth performance varied significantly depending on the physical support used.

Lantern systems consistently delivered better growth, while poches performed poorly, mainly due to biofouling that restricted water exchange. The study indicates that these differences were not linked to feed or stocking density, but to hydrodynamics and system maintenance.

For producers, the implication is straightforward: when spat growth stalls, the limiting factor may be water flow and fouling control.

Dr. Aguiari, from Naturedulis, emphasises that “only by combining scientific research with the deep practical knowledge of farmers can a more resilient, sustainable and prosperous aquaculture be built”.

Selective breeding works when aligned with a developed value chain

Anna Sonesson | NOFIMA

Anna Sonesson | NOFIMA

Selective breeding has also shown clear benefits within the BIVALVI project. A dedicated breeding programme for Manila clam, developed by Nofima in collaboration with Naturedulis, has demonstrated that faster-growing clams can shorten the production cycle by around three months under real farming conditions.

However, according to Anna Sonesson, researcher at Nofima and project lead, genetic improvement only translates into consistent production gains if the value chain — including pre-fattening systems, lagoon management, harvest and distribution channels — does not limit growth.

Sonesson stresses that “selective breeding amplifies good management, but it cannot compensate for inappropriate infrastructure or poorly designed value chains”.

Timing beats prediction in a changing climate

The project also examined mussel populations across different regions and found that reproduction depends on reaching key temperature and food availability thresholds. As noted by Dr. Lynch at University College Cork, one factor stands out for its immediate practical relevance: lunar cycles.

Lynch explains that “peak larval release consistently aligns with full moons and spring tides”, offering farms a predictable window to optimise spat collection for mussels.

Rather than relying on long-term climate projections, the project team suggests that farms can already improve settlement success by aligning rope deployment with these biologically driven spawning windows — a management decision that does not require additional inputs.

Size beats age for spawning

The research showed that some of the oldest mussels that remained relatively small behaved very differently from their faster-growing counterparts. Rather than spawning during a short, well-defined season, these smaller, older individuals showed signs of reproductive activity for much of the year.

This suggests that when growth is limited — by space, competition or environmental conditions — mussels may shift energy away from getting bigger and instead invest more heavily in reproduction.

Microbiology: an emerging piece of the puzzle

The study also observed that different production systems host distinct microbial communities. Systems associated with better growth tended to show a higher presence of potentially beneficial bacteria.

While these findings remain exploratory, Prof. Bonaldo at the University of Bologna notes that farming practices play a key role in shaping microbial dynamics. He points out that “microbial communities are largely shaped by system design and management choices”. Factors such as water exchange, fouling and infrastructure therefore influence the biological environment in which shellfish develop.

A different productivity model

Taken together, the BIVALVI results outline a productivity model that differs markedly from feed-driven aquaculture systems. According to the project partners, productivity gains in shellfish farming are mainly achieved through infrastructure choices that maximise water exchange, proactive fouling management, breeding programmes adapted to fragmented production systems, and operational timing aligned with biological rhythms rather than fixed calendars.