Artificial Intelligence (AI) is no longer science fiction — but neither is it a magic solution. The next productivity gains in aquaculture will not come from smarter algorithms alone, but from better integration, realistic expectations and solid farm management.

For years, AI has been presented as the next major leap for the sector. Promises of “smart farms”, automated welfare control and predictive health systems have become commonplace at conferences, in research projects and in commercial pitches. But where does aquaculture really stand today?

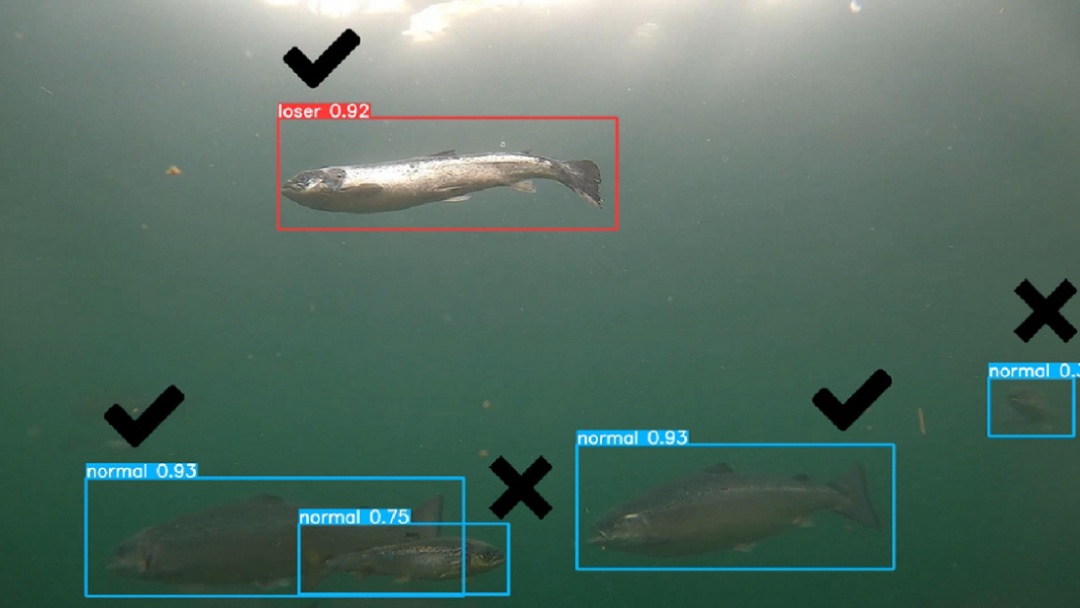

A recent scientific review analysing the use of computer vision and deep learning to interpret fish behaviour offers a much-needed reality check. Its conclusion is clear: AI can already “see” what fish are doing — but turning that information into reliable, day-to-day management decisions remains the real challenge.

Feeding: the most mature application

Among all behavioural applications reviewed, feeding behaviour detection is by far the most advanced and closest to routine use. Vision systems can already identify feeding intensity, surface activity and uneaten pellets with high accuracy, particularly in controlled environments such as RAS or ponds with stable water conditions.

From a production perspective, this is highly relevant. Feed remains the main cost in most farming systems, and behaviour-based feeding control offers a concrete pathway to improve FCR, reduce waste and limit environmental impact. Importantly, the review shows that the main limitation is no longer the algorithm itself, but integration with feeders and farm workflows.

In practical terms, the technology works — but it is not yet plug-and-play.

Stress detection: useful, but not diagnostic

The review also shows solid progress in stress-related behaviour analysis, particularly for hypoxia, ammonia exposure and sudden environmental changes. Alterations in swimming speed, spatial distribution and group cohesion can be reliably detected by AI models.

However, most studies analyse single stressors under controlled conditions, far removed from the complexity of commercial farms, where multiple factors act simultaneously. For this reason, behaviour-based stress detection should be viewed as an early warning tool, not as a substitute for sensors, sampling or veterinary assessment.

Disease, welfare and breeding: still experimental

When it comes to disease detection, welfare assessment or breeding behaviour, the technology is far less mature. Behavioural changes linked to disease are often subtle, non-specific and easily confused with other stressors. Detection of aggression or breeding behaviour exists, but only for specific species and highly controlled systems.

For now, these applications remain largely research-driven, with limited short-term value for most producers outside hatcheries or broodstock units.

The real bottleneck: deployment, not AI

AI performance in aquaculture is now constrained more by data and infrastructure than by algorithms. Underwater visibility, variable lighting, biofouling, annotation costs and computing requirements continue to limit real-world deployment.

Many models still depend on powerful hardware and farm-specific datasets, making large-scale standardisation difficult. As a result, solutions that perform well in pilot trials often struggle to scale across sites, species or production systems.

A decision-support tool, not a replacement

In 2026, AI in aquaculture should be understood as a decision-support tool, not an autonomous management system. Its greatest value lies in supporting feeding decisions, detecting abnormal behaviour early, and complementing sensors and operator experience.

The future clearly points towards hybrid systems, combining vision, environmental sensors and human oversight, rather than fully automated “black box” solutions.

This review does not show that AI will automatically improve welfare, eliminate disease or replace farm staff. It does, however, confirm that the technology has moved beyond theory — at least in some key areas.