The use of microalgae as a tool for carbon dioxide (CO2) capture has long been presented as a promising option within decarbonisation strategies. However, significant uncertainty remains between theoretical potential and effective industrial application.

A recent study published in the Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering helps to narrow this gap by providing concrete data on how carbon is dissolved, becomes available, and is ultimately captured in microalgae-based systems.

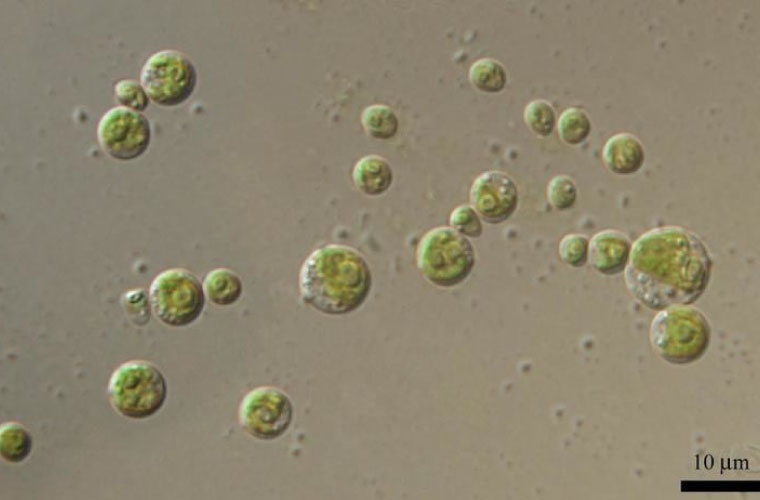

The study examines the behaviour of two halotolerant strains of Chlorella vulgaris under different carbon and nutrient supply regimes. Beyond its biological interest, the value of the work lies in its process-oriented approach, as it helps to identify which factors truly limit CO2 capture and which are secondary from an operational standpoint.

One of the study’s clearest findings is that increasing CO2 supply does not guarantee higher capture efficiency. The authors show that even with continuous CO2 inputs at 1%, fixation efficiency falls below 5%, as a substantial proportion of the supplied carbon is not incorporated into biomass and is lost from the system.

This result challenges approaches based solely on CO2 injection – such as the direct use of flue gases – without a system design that maximises effective utilisation. In practice, CO2 ceases to be the main limiting factor and instead becomes an underutilised resource.

In this context, the study shifts the focus to another key element: nutrient availability. The results show that when nitrogen and phosphorous are depleted, the ability of microalgae to capture carbon is significantly reduced, even if CO2 is present in excess. In other words, without sufficient nutrients, system performance declines sharply.

This observation reinforces the rationale for integrating microalgae systems with nutrient-rich streams, such as aquaculture effluents or wastewater, rather than relying on stand-alone systems designed solely for carbon capture. In such cases, CO2 capture is only efficient when it forms part of a broader treatment and resource-recovery system.

Another relevant outcome of the study is that not all strains behave in the same way. Although both strains belong to the same species and originate from similar habitats, their responses to carbon and nutrient supply differ. One strain shows greater sensitivity to increased CO2 availability, while the other responds more strongly to nutrient enrichment.

For the sector, this underlines the importance of strain selection based on process objectives and cautions against generic approaches that overlook biological variability. In productive systems, the choice of biological material can be just as critical as system design itself.

The study also compares passive and active carbon supply strategies, introducing an additional operational consideration. Passive systems, without continuous CO2 injection, offer lower overall carbon availability but achieve higher relative fixation efficiency, meaning a larger proportion of the available CO2 is converted into biomass. Active systems, by contrast, generate greater carbon availability but use it less efficiently.

From an operational perspective, this balance between availability and efficiency is central to assessing the real viability of microalgae-based systems, particularly in contexts where energy costs and operational simplicity are decisive factors.

Despite the relevance of these findings, the study does not propose a solution that is ready for industrial deployment. The authors themselves acknowledge that technical and economic validation will be required before implementation under real operating conditions can be considered.

In this respect, the work – carried out with the participation of IMEDEA (Spain) – points to potential applications such as wastewater treatment, where naturally available nutrients could improve system performance.

Furthermore, the study highlights a crucial advantage: despite efficiency challenges, microalgal biomass theoretically captures ~1.8 g of CO2 per gram—a capacity competitive with, or even superior to, hazardous chemical solvents like NaOH or MEA.

In practical terms, the study does not demonstrate that microalgae are an immediate solution for CO2 capture in aquaculture or RAS environments. What it does provide is quantitative evidence that tempers an often overly optimistic narrative. The results make clear that CO2 itself is not the primary bottleneck.

Nutrient availability, strain selection, system efficiency and – above all – integration with existing production streams will determine whether CO2 capture using microalgae can become a genuinely operational tool for the sector, or whether it will remain, for now, an attractive but difficult-to-realise promise.

Reference:

Shuhaili, F., Srinivasan, M., Vijayaraghavan, R., Segura-Noguera, M., Lakshmanan, U., Prabaharan, D., & Vaidyanathan, S. (2025). Dynamics of carbon dioxide capture in two halotolerant strains of Chlorella vulgaris. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 13, 120493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2025.120493