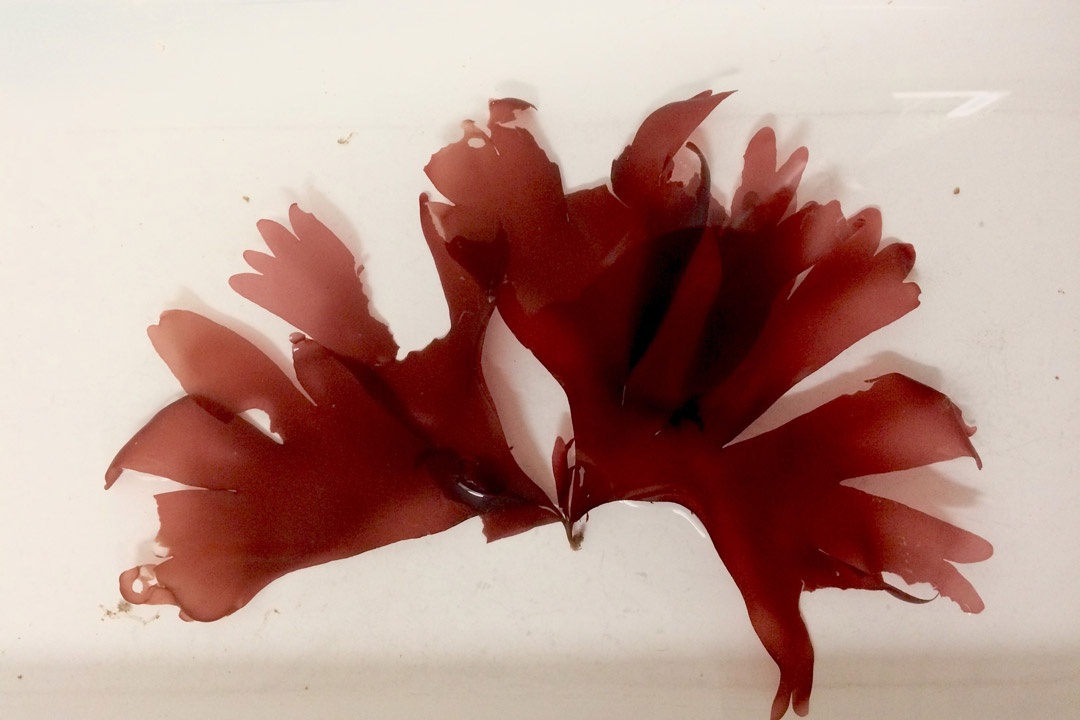

For years, red seaweeds such as Palmaria palmata have been presented as a “future ingredient” for aquafeeds. Their nutritional potential is well known. The real bottleneck has never been biology — it has been processing.

A new study published in Phycology puts its finger squarely on that problem and points to a realistic first step forward: high-solids alkaline processing.

According to the authors, if red seaweed is ever going to move beyond niche inclusion levels, it must stop behaving like an indigestible fibre block and start behaving like a feed ingredient. In that context, how it is processed matters more than which seaweed species is chosen.

The study shows that treating Palmaria palmata under high-solids conditions — with very little free water — using a short alkaline autoclaving step can significantly reduce structural fibre and increase the fraction of soluble compounds. In practical terms, this means less rigid cell walls, better access to intracellular nutrients, and a material that is easier to integrate into feed manufacturing workflows.

Crucially, everything remains in a single solid fraction. There are no liquid extracts, no phase separation, and no lab-style downstream processing that feed mills cannot realistically adopt.

Most previous seaweed processing studies rely on large volumes of water. That approach may work in the lab, but it creates serious problems at scale: dilution, higher energy demand, effluent handling, and incompatible logistics.

High-solids processing flips that logic. It treats seaweed as a feed raw material, not as a source of extracts. That shift alone makes the concept far more relevant for feed formulators looking for functional ingredients, IMTA producers considering pre-processing at origin, and companies trying to align sustainability narratives with industrial reality.

The paper also sends a clear signal on enzymes. Under high-solids conditions, alkaline pretreatment does most of the work. Commercial carbohydrase enzymes add little unless very high doses are used, once again highlighting the lack of macroalgae-specific enzymatic solutions suitable for industrial use.

The authors are careful not to oversell the results — and so should the sector.

This is not proof that red seaweed improves fish growth, digestibility or performance. No feeding trials were conducted. Ash and mineral content, a well-known limitation of seaweeds, remains unresolved. And the economic and environmental costs of alkaline processing still need to be assessed.

What the study does provide is something the sector has been missing: a technically credible processing route that could make red seaweed usable at scale.

Red seaweed will not enter aquafeeds because it is “natural”, “blue” or “sustainable”. It will enter when it can be processed in a way that fits feed manufacturing constraints.

This study suggests that high-solids alkaline processing may be one of the first realistic steps in that direction — not the final solution, but a necessary one.